Platypuses by sea

Betty, Cecil, and Penelope's North-American stunt.

In February of 1946, David Fleay received another curious request. Fairfield Osborn, President of the New York Zoological Society, asked Fleay to send a platypus family to New York — only the second journey of its kind.

In response, David Fleay captured 19 more platypuses over three weeks. Of these, only three fateful platypuses were chosen to be transported to the Bronx Zoological Park in New York. Fleay christened them as Betty, Cecil, and Penelope [3].

Through the Archives

The 1947 Transport

The Australian Museum’s Fleay archives hold a wealth of exciting new insight into the 1947 voyage of the platypus and their North American stardom.

The activities of Betty, Cecil, and Penelope were not meticulously recorded in a midshipman’s logbook as with Winston the platypus in 1943. However, through various film prints and negatives, the Fleay archives uncover an exciting journey across the Atlantic Ocean aboard the M.V. Pioneer Glen, a newly constructed American cargo ship. By working through the Fleay archives, we become closely acquainted with Fleay’s motley crew, which consisted of:

David Fleay

Sigrid Fleay

Boatswains

Ship officers

platypus handlers

Chefs

Messboys

Vampire bats

South-American opossums

Two-toed sloths

at least one child

& three bewildered platypuses

One thing was certain - this journey to America was not a lonely one [3].

✰ Platypus DiplomacY ✰

Given that Australia was barely two years out of World War II, the case for the diplomatic platypus is rather convincing. America and Australia developed a very close friendship following the war. Security alliances such as the 1951 ANZUS Treaty and the abroad education offerings under the Fulbright Program of 1946, as well as the strong cooperation in the founding of the United Nations in 1945, were all core examples of the growing Australia-America allyship [9].

Australia’s key ally before World War II was the United Kingdom. Following WWII, the priority shifted towards America [2]. One way to understand this shift is through the concept of platypus diplomacy; the three cases of platypus transport following WWII occurred solely in the United States [2]. ⠀⠀⠀

The New York Zoological Society’s request for platypuses provided Australia with the opportunity to strengthen political relations with the United States, by using the uniqueness of the platypus as a way of invigorating the American public [1,2].⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Diplomacy?

Even though the case for the diplomatic platypus is rather convincing, the diplomatic outcome of David Fleay’s 1947 transport to New York was far less than direct.

Given the sensitive nature of the platypus, David Fleay spent almost a year preparing for their travel. However, not even he was exempt from the stringent restrictions of Australian customs [3]. Merely a week before their planned departure in March of 1947, Fleay received a devastating government notice:

Shipment of three platypuses to United States not in the national interest. Export forbidden.

Senator Ben Courtice for Trade and Customs, 1947

This was problematic, to say the least...

However, after a desperate meeting with Senator Ben Courtice, Trade and Customs revoked their original ruling, and the journey of Fleay and Co. was underway! With apprehension, the platypuses were flown from Melbourne to Brisbane, before they were transferred on board the M.V. Pioneer Glen. The ‘Pioneer Glen Zoo’ set sail on the 29th of March, 1947 [3].

Journey to the Bronx

12,000 precarious miles

As of 1947, only David Fleay had managed to successfully breed platypuses in captivity.

Thus, international fame was all but guaranteed to a sanctuary that would succeed in platypus breeding, especially if it occurred outside of Australia.

David Fleay was also in charge of ensuring that the platypuses lived comfortably in transit to their new North American home.

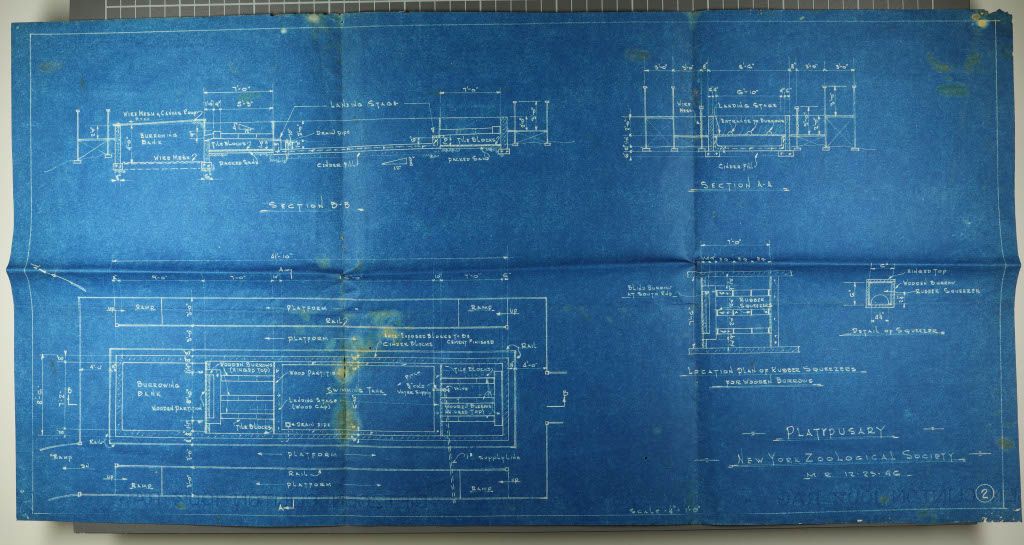

The platypusary was a portable enclosure that had to be viable for cross-continental transport aboard the Pioneer Glen.

It was also viable as a zoo exhibit that allowed visitors to catch a glimpse of the elusive duck-billed platypus in action.

However, designing these enclosures was no simple feat.

The design of the New York platypusary was intricately detailed by Fleay in a series of original blueprints housed by the Australian Museum.

By creating a comfortable environment for the creatures, Fleay hoped to breed the platypus once again, as he had done with Jack and Jill in 1943.

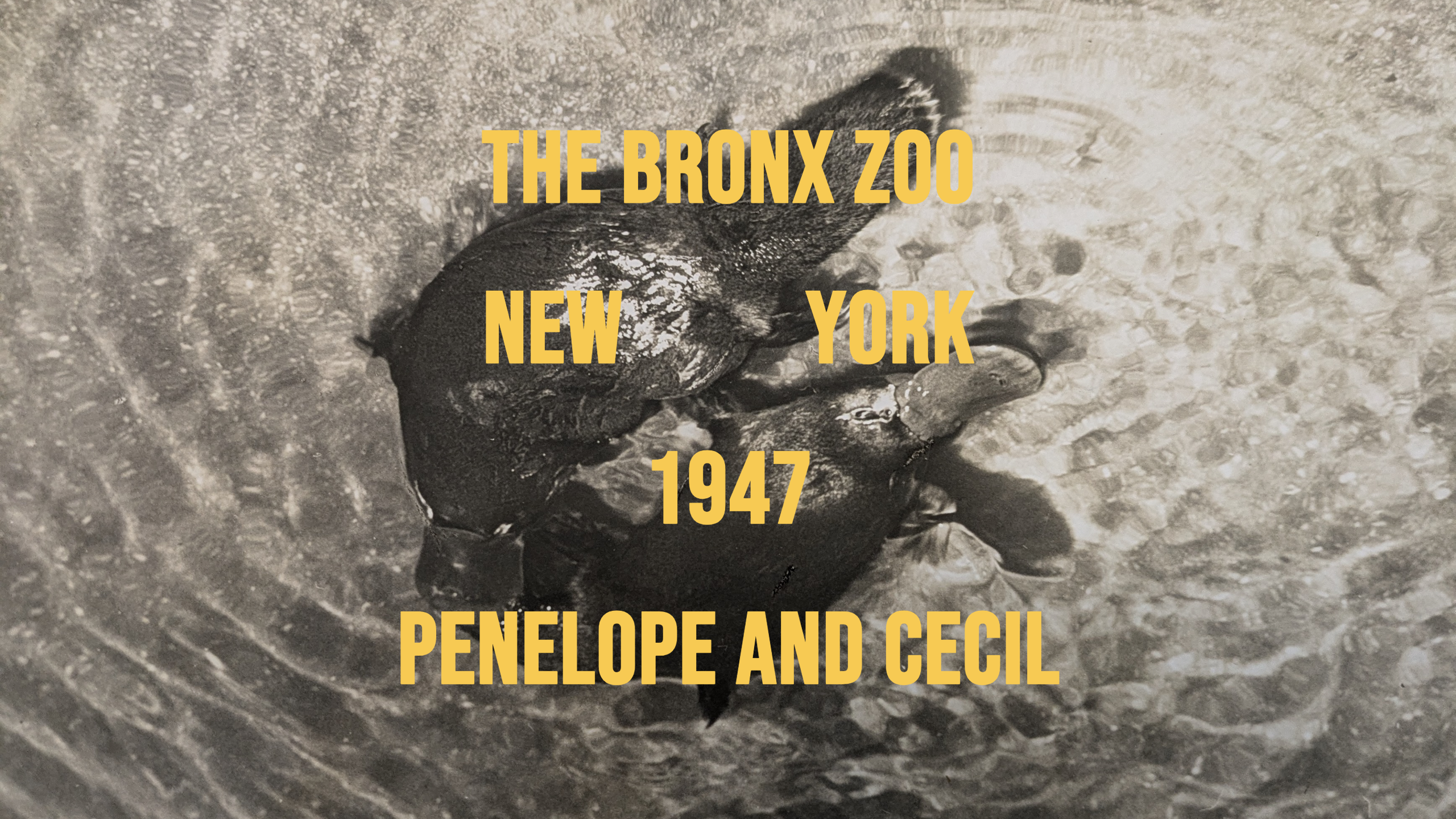

After rough seas and a worm crisis, the three unknowing creatures arrived on American shores on the 25th of April in 1947. Betty, Cecil, and Penelope were to spend the rest of their lives in the limelight of the Bronx Zoological Park[3].

Within the walls of their bespoke platypusary, both American and Australian publications became smitten by the zoo’s newfound star animals. Betty, Cecil, and Penelope became something more akin to the starlets of Hollywood, living under the watchful eye of the publicity, rather than prudent political officials.

'The radio, magazines and press have all ‘gone platypus.’ We were sure that they would take America by storm.

So they have.'

Fairfield Osborn, President of the New York Zoological Society, 1947

However, not all was smooth sailing.

Six months into their relocation, David Fleay writes that Betty, the older female platypus, tragically perished, possibly from a cold.

Betty’s death was at once a symbolic and physical one, as most newspapers and publications go on to focus on the courtship between Cecil and Penelope.

David Fleay, Betty - unique among female duckbills in acquiring a test for steamed-egg preparation, 1947, Also housed in Australian Museum Fleay Archives, in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with Duckblls, by David Fleay (Jacaranda Press), 74.

David Fleay, Betty - unique among female duckbills in acquiring a test for steamed-egg preparation, 1947, Also housed in Australian Museum Fleay Archives, in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with Duckblls, by David Fleay (Jacaranda Press), 74.

In contrast to the tabloids, it is obvious that Fleay reserved much affection for Betty

In Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with Duckbills, Fleay recounts how Betty:

acquired a taste for egg custard, and then South American cockroaches

returned from the brink of death

and refused to leave when released into the wild.

One peculiar outcome of Fleay’s 1947 platypus transport was the imprint of American post-war culture onto the unknowing Australian monotremes.

This popular culture revelled in the interactions between monogamous partners and families, one that birthed the first instances of reality television as we know it today. In their newfound celebrity status, Cecil and Penelope’s supposed romantic relationship came into focus as a pressing interest of the general public [6]. This was a phenomenon that stretched all the way back across the Atlantic.

‘Their courtship - all-night orgies of love and copious quantities of crayfish and worms - lasted four days ’ [7]

Peter Hastings for the Daily Telegraph, 1953

'Penelope came here with her husband, Cecil, from Australia in 1947.' [8]

The Bayonne Times, 1963

‘Penelope does not like Cecil, so their engagement is off - at least until next autumn’’ [5]

The Kalgoorlie Miner, 1953

‘[Penelope and Cecil were] star performers - touchy, obstinate, and temperamental.’ [7]

Peter Hastings for the Daily Telegraph, 1953

For any casual reader, it was also obvious that these curious creatures were divas - spoilt and treated like royalty within their bespoke platypusary, with a very particular taste for colour.

Officials raised the tank sides ...

lowered them ...

widened landing platforms ...

repainted them ...

toned down the Public address system ...

Refused entry to women in bright clothes ...

Lined the tank sides with oiled plywood

and because Cecil nearly had convulsions

Relined it with untreated

plywood [7]

Courtship between Cecil and Penelope was tried time and time again by the zookeepers - the publicity keenly followed.

However, In July of 1953, Penelope’s behaviour changed...

Instead of her usual hatred toward Cecil, she was more peaceful and accepting of him. She was seen moving Eucalyptus leaves toward her burrow, retreating there for a week before emerging for more resources. These were common signs of pregnancy... Penelope was subsequently given more food. The baby (known as a puggle) was expected to emerge from the burrow in around 17 weeks.

A week before the expected emergence, zookeepers scrambled through Penelope’s burrow, seeking to confirm their suspicions of Penelope’s pregnancy. The zookeepers expected to find Penelope with either eggs or a new puggle during this investigation. Luckily, the zookeepers came prepared. Towels, a scale, several zookeepers and even a “zoo ambulance” were prepared for this exciting excavation.

However, all that was found was a slightly-tempered Penelope. Disappointment loomed as the zookeepers realised they had been “duped”.

“What a racket she [Penelope] was working. Getting double rations for five months. No more of that for her.”

Fleay also famously received a letter from Penelope stating:

“No babies this year. There's always next year.”

The American and Australian media companies loved this story. Tailoring it as a ‘staged pregnancy’, used by the foxy Penelope to escape Cecil, gain more food, and enjoy the comfort of her burrow.

Fleay, however, was outraged by this treatment of the unknowing creatures.

As a true testament to his love for the platypus, Fleay wrote to The Age, an ongoing Victorian publication. In this short, but impassioned commentary, Fleay rebukes portrayals of Penelope as a ‘great deceiver’ with sinister intents:

‘[Penelope was] shamefully maligned’ - rather, she was ‘always an ordinary, straight-forward lady platypus’ [4]

Was Penelope actually pregnant?

Fleay suggests that perhaps, Penelope was indeed pregnant, and the zookeepers at the Bronx Zoo were simply ignorant of the fact. Was it possible that she did lay some eggs in the Summer of 1953, only for the eggs or puggle to die shortly after? Whether this was the case is unclear. Nonetheless, the public eye remained largely on the malicious character of Penelope the Platypus.

Fleay’s discontent with Penelope's treatment is completely consistent, especially when we consider the level of affection and respect he reserved for Jack and Jill, the parents of the first platypus bred in captivity, Corrie. In his 1944 publication, We Breed the Platypus, Fleay recounts the story of Jill in the Healesville Sanctuary, following her attempted escape.

'That night the beam of a spotlight picked her out where she frolicked, like a tiny hippopotamus, among the tadpoles of a neighbouring lily-pond.' [5]

David Fleay in We breed the platypus, 1944

'After a few minutes, it was noticed that Jack seized Jill’s tail in a firm grip with his bill and the two animals swam slowly in a processional circle.' [5]

David Fleay in We breed the platypus, 1944

There is a tangible affection in Fleay's prose, in stark contrast to the scathing dramatics of the 1953 newspapers. Furthermore, when he speaks of Jack and Jill’s mating ritual, he speaks in narrative through the plain language of ‘science’, rather than the sensational jargon of the tabloids.

While diplomacy may have been the overt purpose of the 1947 journey, the Australian Museum's Fleay archives uncover something much more revealing of Fleay’s intents surrounding the platypus.

Detailed platypusary plans, images of a fully-equipped Pioneer Glen, and personal recounts of Fleay's encounters demonstrate a dedication to the creature that would be absent for anyone less passionate. Platypuses were not merely an attraction worth exhibiting to the world, but creatures worthy of dignity and respect. Instead of solely building fame for the platypus, Fleay truly cared for their well-being and wanted to construct scientific knowledge that was reflective of their behaviour.

Bibliography

1. Arup, Tom. 2014. “The Rise and Influence of Koala Diplomacy.” The Sydney Morning Herald. December 26, 2014. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/the-rise-and-influence-of-koala-diplomacy-20141224-12dj2b.html.

2. Cushing, N., and Markwell, K. “Platypus Diplomacy: Animal Gifts in International Relations.” Journal of Australian Studies 33, no. 3 (2009): 255-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050903079664.

3. Fleay, David. “The Saga of Cecil, Penelope and Betty - Platypuses by Sea to New York.” In Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with Duckbills, Edited by D. Fleay (Jacaranda Press, 1980)

4. Fleay, David. “Penelope Platypus in New York.” The Age. January 30, 1954. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/206088241?searchTerm=penelope%20platypus#.

5. Fleay, David. "We Breed the Platypus." Boolarong, 1944.

6. Kalgoorlie Miner, “Plans for Platypus Wedding Postponed,” Kalgoorlie Miner, June 30, 1953, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article256894149.

7. Meyerowitz, Joanne. “The Liberal 1950s? Reinterpreting Postwar U.S. Sexual Culture.” In Gender and the Long Postwar: Reconsiderations of United States and the Two Germanys, edited by K. Hagemann and Sonya Michel (John Hopkins University and Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2014).

8. Peter Hastings, “Troubled Mating of Cecil and Penelope,” The Daily Telegraph. July 18, 1953, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-daily-telegraph-troubled-mating-of-c/137529414/.

9. The Bayonne Times, “Zoo Officials Dig for Platypus’ Offspring,” The Bayonne Times. November 5, 1953, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-bayonne-times-zoo-officials-dig-for/137529209.

10. U.S. Department of State. 2022. “U.S. Relations with Australia - United States Department of State.” United States Department of State. July 23 2024. https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-australia/.