The death of

Winston THE platypus

Who is to blame?

During WWII, an unlikely passenger traveled from Australia across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, at the request of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill.

Who was this passenger?

Winston the platypus.

Waving goodbye on the 2nd of October 1943, Winston boarded the M.V. Port Phillip and set sail on the high seas...

...across the Pacific Ocean to Panama with 50,000 worms in tow...

...and then onwards over the Atlantic to Liverpool.

However, our Australian passenger never made it to Liverpool to meet the man he was named after...

On the 4th November 1943, just two days before the boat reached its destination,

DISASTER STRUCK

The incident was kept secret during the war to avoid public disappointment and any outcry from Australian zoologists[1]. Consequently, only a few British and Australian politicians and zoo staff actually knew about Winston's death at the time.

However, in the aftermath of WWII, the news spread and the same question consumed crowds across the world:

WHODUNNIT?

How did Winston die?

newsPAPERS REPORTED WINSTON'S VOYAGE AND DEATH

...AND EACH ONE NAMED A CULPRIT

ARTICLES WERE DOMINATED BY THEORIES OF GERMAN SUBMARINE interference

...AND the M.V. Port Phillip's responding DEPTH CHARGES.

Aside from these journalistic, sensationalised accounts, other sources named alternative suspects for the death of Winston.

Stories from the Ship

According to the ship Captain's report, Winston's death "was due partly from shortage of worms and partly from fright"[2].

As the journey to Liverpool was delayed at various ports, Winston's food was rationed from 750 worms a day to 600 to preserve declining stores.

Additionally, the Captain's report mentions the detonation of depth charges on the 4th of November which would have distressed Winston.

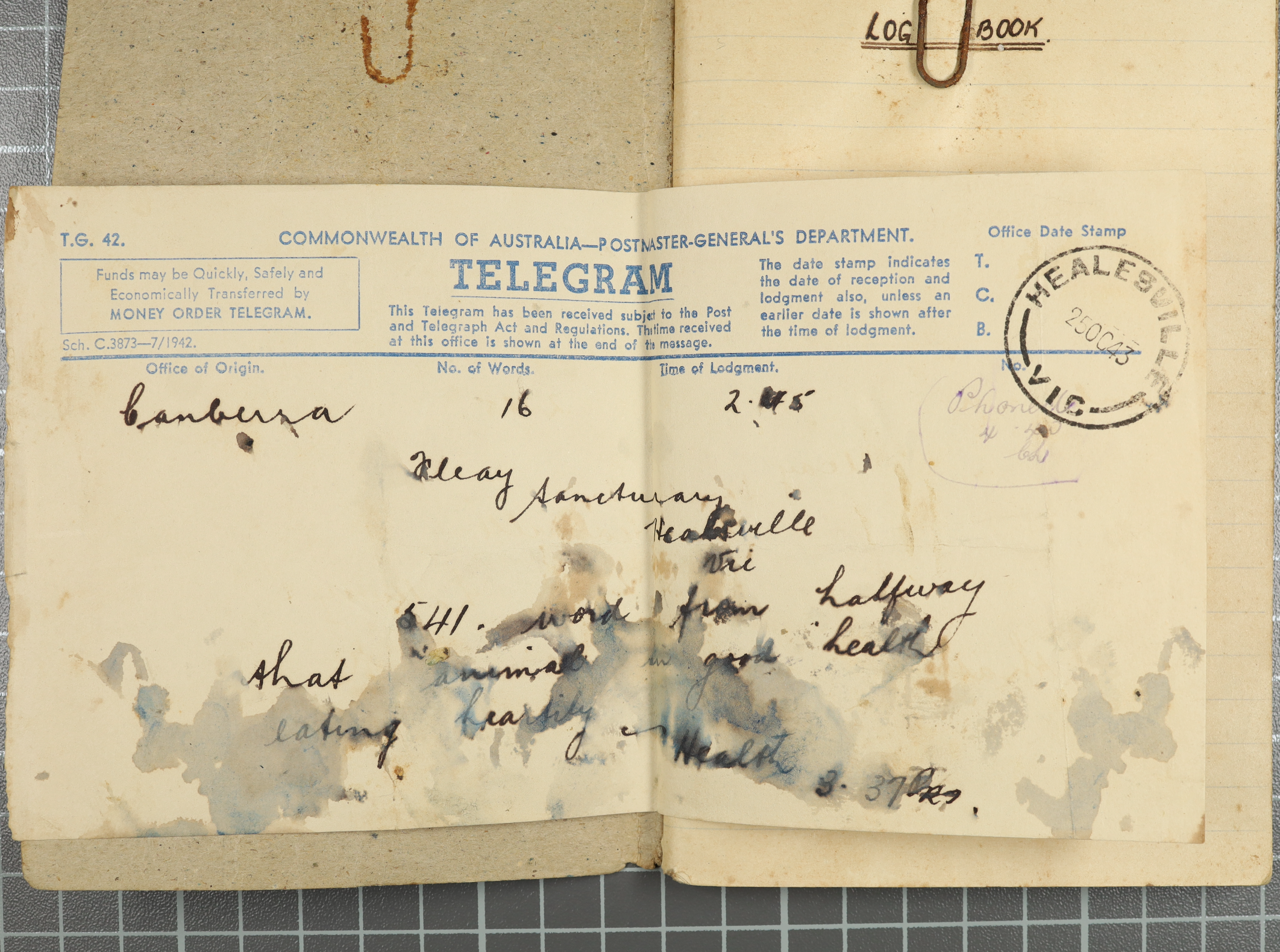

However, first-hand data from the voyage has recently been uncovered which could point to yet another culprit.

the midshipman's log

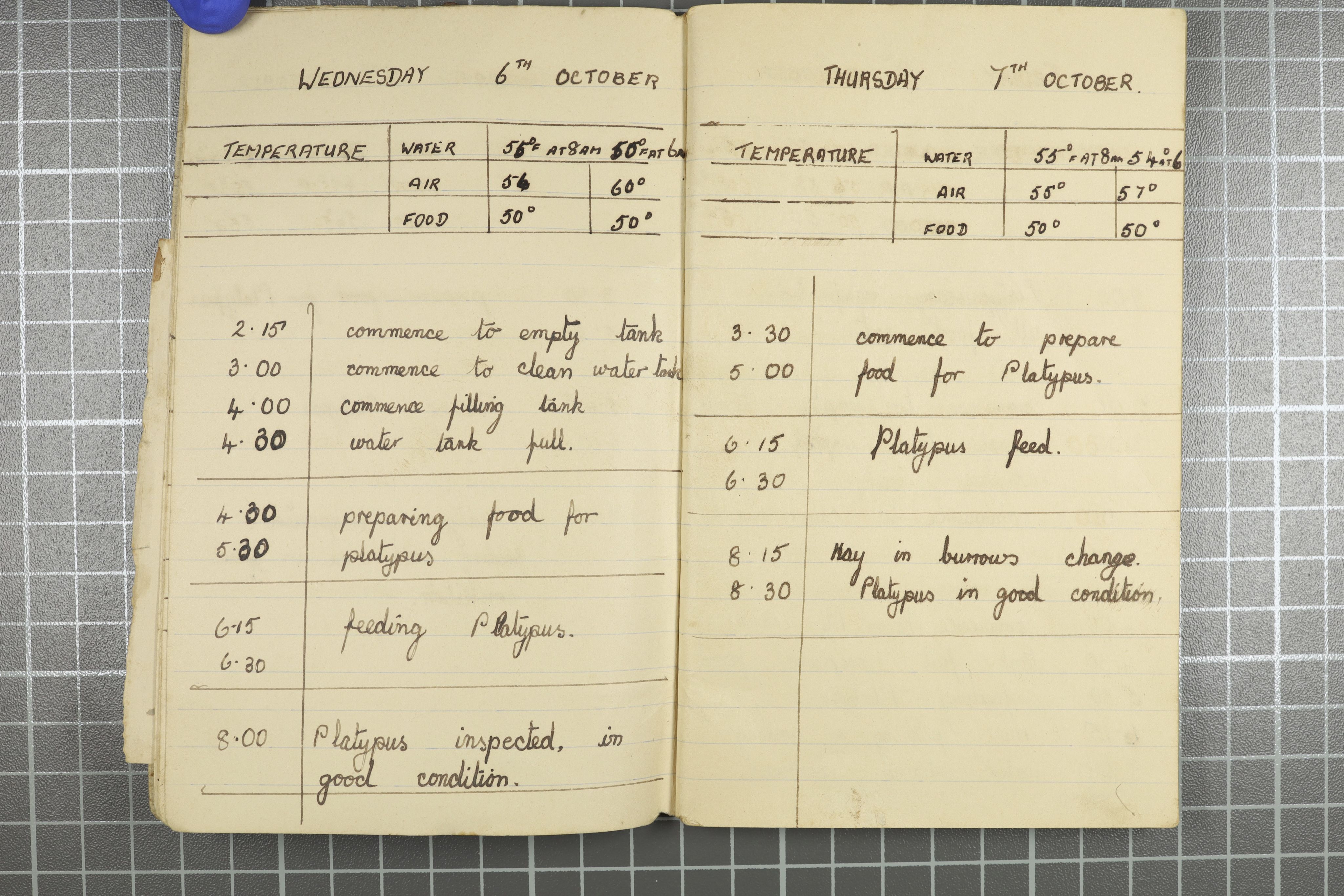

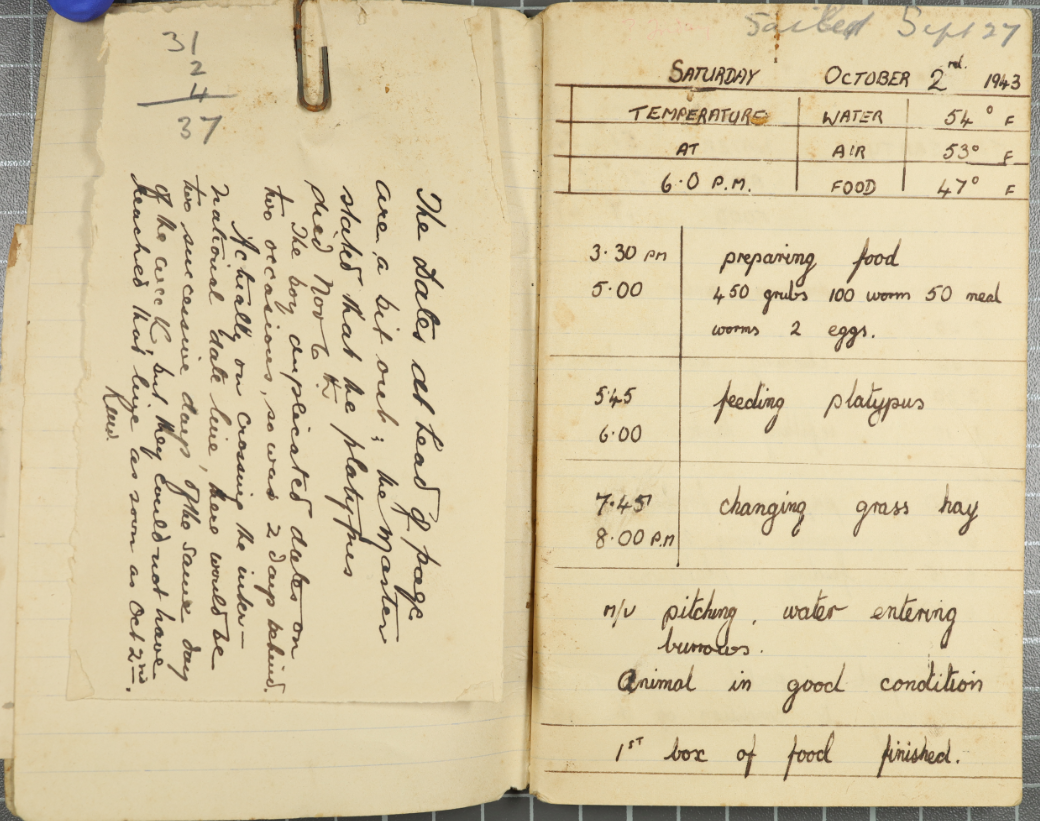

Throughout the voyage, Winston was checked on daily and data was recorded in a logbook detailing:

- feeding times

- platypusary cleaning times

- temperatures of water, air and food

No explicit comments were made in regard to the means of Winston's death, but the story this data tells is far less violent and far sadder than a German submarine or depth charge.

Midshipman's Log, pp.9-10, AMS731, Australian Museum Archives.

Midshipman's Log, pp.9-10, AMS731, Australian Museum Archives.

WHEN GRAPHED, THE DATA SUGGESTS A new SUSPECT for Winston's death:

heat stress

this is a graph of the food, air and water temperatures on the ship, measured at 8am and 6pm daily.

It shows a period of roughly one week where the AIR AND WATER temperatures exceeded 27°C.

THIS hot period would have occurred WHEN THE ship PASSED through THE caribbean, close to THE EQUATOR.

Whilst these temperatures don't seem extreme for us humans,

they're very high for platypuses.

Also keep in mind that these temperatures were measured during cooler parts of THE day,

And they therefore don't represent the maximum daily temperatures Winston experienced.

TO appreciate THE SIGNIFICANCE OF this DATA WE NEED to understand SOME BIOLOGY

The body temperature of the platypus is 32°C

Platypuses, like other mammals, are able to maintain a steady body temperature using thermal homeostasis.

This means that they can adapt and balance their body temperature in response to changing ambient temperatures.

In the freshwater Australian environments where platypuses live, this ranges from approximately 20°C down to below 0°C[3].

In environments warmer than 25°C, platypuses CANNOT regulate their body temperature

As the ambient temperature approaches the body temperature of the animal, they are more susceptible to heat stress in these environments[4].

Symptoms of heat stress can include blood vessel swelling and temporary loss of consciousness.

Research suggests that brief exposure to temperatures greater than 34°C can be fatal for platypuses.

KEEP THEM COOL!

Accordingly, modern recommendations regarding platypus transportation advise against ever exposing the platypus to temperatures exceeding 27°C[5].

Our Hypothesis

In light of this information about thermal homeostasis in platypuses, we believe that the data from the shipman's logbook demonstrates that Winston likely died from prolonged heat stress during his trip.

Contrary to the popularised narratives about German interference, which lack sufficient evidence, our analysis shows that heat stress alone would have been enough to kill Winston.

However, it is important to note that food restrictions and the shock of a depth charge, in combination with heat stress, likely had an additional impact on Winston's wellbeing and together contributed to his demise.

why would Winston Churchill even want a platypus?

At the time, Europe was still fascinated with ‘the exotic’ and animal collections were symbols of British imperial prowess, as well as being sources of entertainment and scientific study[6].

Winston Churchill had a keen interest in such menageries, and over his lifetime he collected a white kangaroo, a budgie, black swans, and a lion which he kept at London Zoo.

After David Fleay's successful breeding of platypus in captivity, these animals became an ever popular symbol of Australia.

For Mr Churchill to obtain a platypus, it would not only be a great zoological achievement, but also emphasise Australia's history as part of the British Empire.

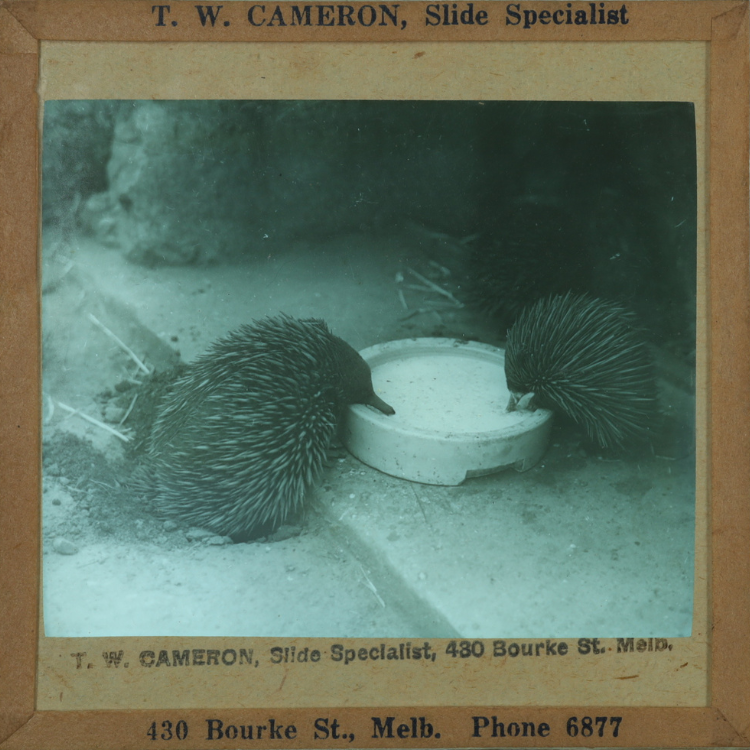

Two echidnas eating from bowl, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/139, Australian Museum Archives.

Two echidnas eating from bowl, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/139, Australian Museum Archives.

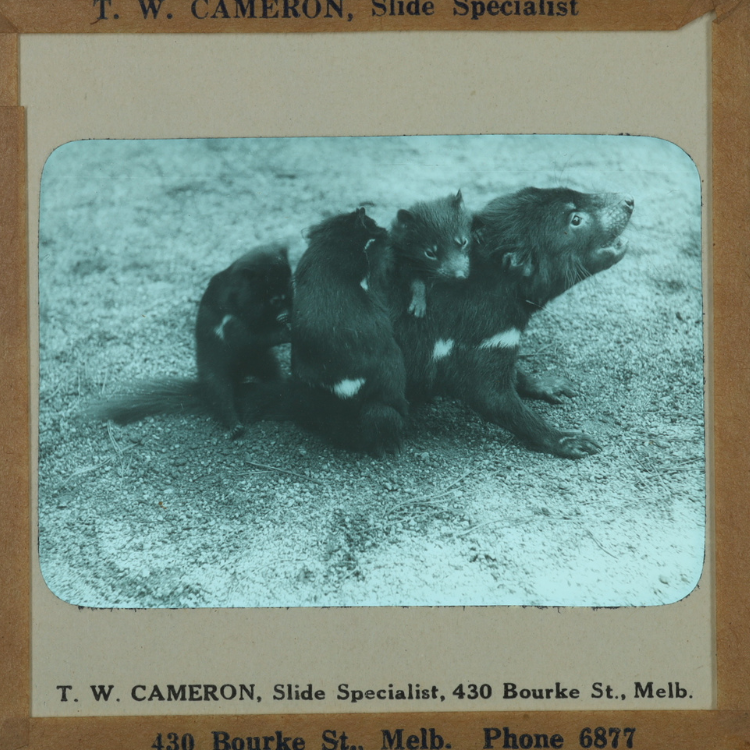

Tasmanian Devil with three infants, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/148, Australian Museum Archives.

Tasmanian Devil with three infants, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/148, Australian Museum Archives.

Platypus, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/140, Australian Museum Archives.

Platypus, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/140, Australian Museum Archives.

Platypus held on palm of hand, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/127, Australian Museum Archives.

Platypus held on palm of hand, Lantern slides of Australian fauna by David Fleay, AMS729/127, Australian Museum Archives.

In the context of WWII, this could have been a reminder for Australia to remain steadfast to their Commonwealth allies or as a morale boost during wartime.

Alternatively, Churchill might have just really wanted a cool new animal for his collection, creating an opportunity for Australia to ask for a favour in return.

"Then again might not the little animals be urgers for more planes and guns? Even Ornithorhynchus was entering the war effort."

David Fleay in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with duckbills (1980)

Regardless of Churchill's intent when requesting the platypus, Australian politicians likely agreed to avoid any tension with Britain in a time of war. And after all, who could say no to the British Prime Minister?

And so it was that a certain Mr David Fleay was contacted to arrange the capture and transport of platypuses to England for the first time. Initially, Churchill had requested for six platypuses to be sent over but Fleay negotiated it down to a single animal. Transporting just one platypus would be much more manageable, especially in terms of food and space requirements on the boat, compared to a large group of six.

"... six freshly captured platypuses, housed on a ship (the only

form of transport envisaged), would suffer an immediate form of hysteria, accelerating into hopeless stampede and early death."

David Fleay in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with duckbillsIn consultation with experts, a custom transportable platypusary was built for the five-week boat journey and no expense was spared. Funded by Prime Minister Curtin's government, Winston's temporary home was hailed by Fleay as "the most intricate, comfortable and self-contained duckbill habitation...that could be constructed". [7]

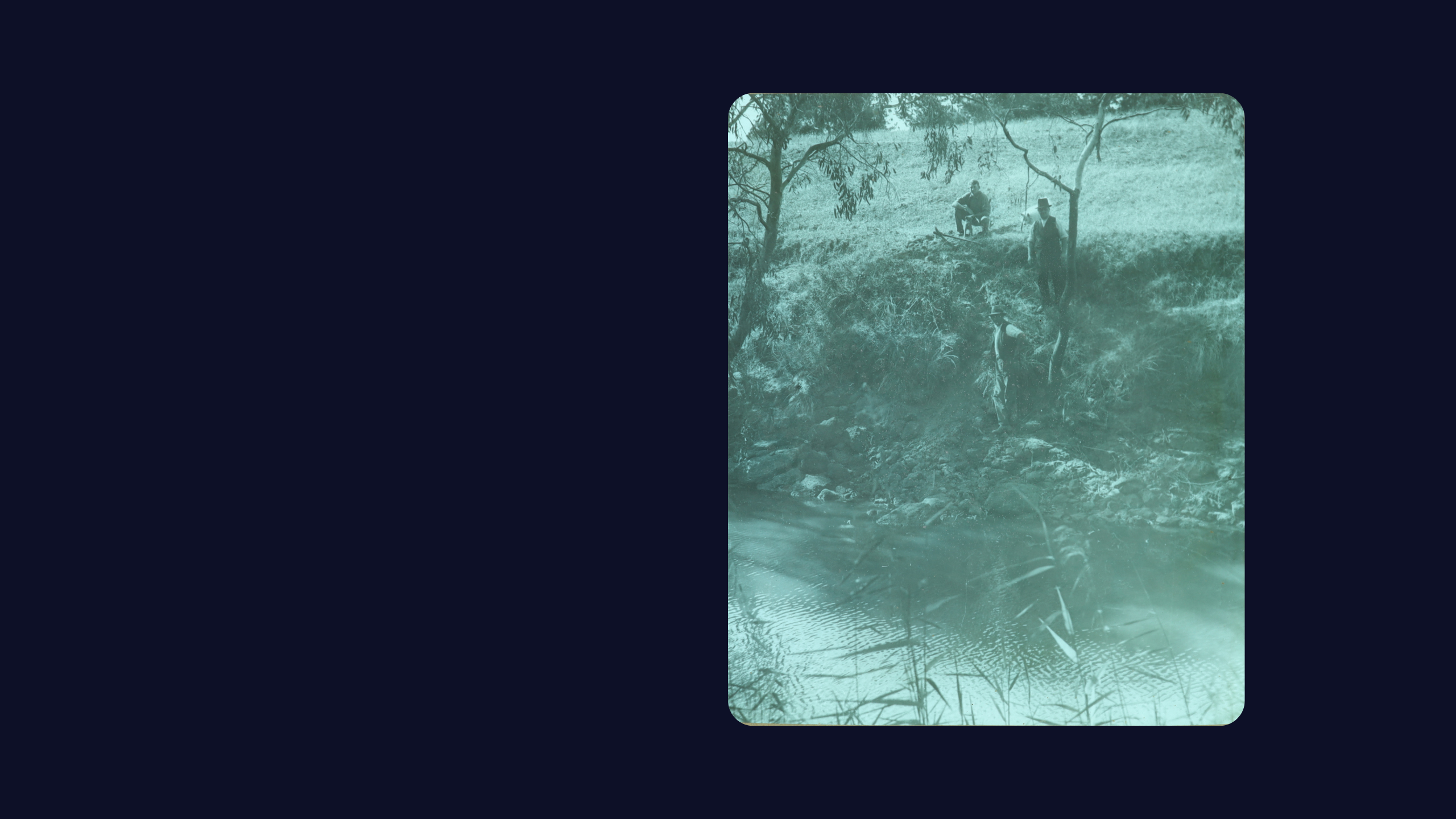

Fleay himself caught little Winston from Watts River in Victoria and domesticated him over the next seven months. Intended to be the first platypus to ever set foot in Europe or the UK, Fleay had high hopes for Winston and was confident he would survive the journey.

"Truly a little beauty, he well deserved his christening, and obviously possessed all the attributes of self-possession and good condition so essential to the trials ahead."

David Fleay in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with duckbills (

Aftermath

When news of the Winston's fate reached Churchill, he was greatly disappointed and Winston's body was sent to the Royal College of Surgeons to be taxidermied[8].

David Fleay himself didn't hear of Winston's death until three weeks after, on the 22nd of November, and even then the platypus' story would not reach radio or newspapers until much later.

Though this attempt to send platypuses to the UK was unsuccessful, it still marks an unbelievably unique diplomatic and zoological collaboration between Britain and Australia. Given the postwar coverage of Winston and the excitement future platypus voyages generated, there is little doubt that this would have been an incredibly beneficial diplomatic endeavour, had it been successful.

"It was so obvious that, but for the misfortunes of war, a fine, thriving, healthy little platypus would have created history in being number one of its kind to take up residence in England."

David Fleay in Paradoxical Platypus: Hobnobbing with duckbills (1980)

Bibliography

1. Lawrence, N. "The Prime Minister and the platypus: A paradox goes to war." Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 43 (2012): 292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.09.001

2. W.J. Enright's letter to London informing Churchill of platypus death, 12 November, 1943, Personal: Family; Pets and other animals; London Zoological Society, CHUR1/58B #306, The Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust.

3. Nicol, S.C. "Energy Homeostasis in Monotremes." Frontiers in Neuroscience 11 (2017): 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00195

4. Smyth, D.M. "Temperature regulation in the platypus, Ornithorhynchus anatinus (shaw)." Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 45, no.3 (1973): 705. https://doi.org/10.1086/physzool.51.1.30158659

5. Booth, R. and Connolly, J. "Platypuses." In Medicine of Australian Mammals, edited by L. Vogelnest and R. Woods, 103-132/ CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood VIC, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238587080_Medicine_of_Australian_Mammals

6. Lawrence, N. "The Prime Minister and the platypus: A paradox goes to war." Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 43 (2012): 291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.09.001

7. Fleay, D. PARADOXICAL PLATYPUS: Hobnobbing with duckbills. The Jacaranda Press, 1980: 53.

8. Churchill's telegram to Evatt, 21 November, 1943, Personal: Family; Pets and other animals; London Zoological Society, CHUR1/58B #310, The Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust.